Article Eleven:

The Cube Root of Entropy

By Gary Lee-Nova, Bob Arnold, Dennis Vance

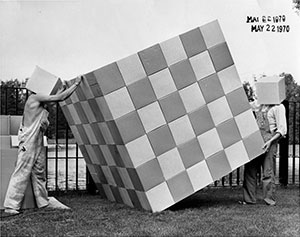

Site Specific interactive installation, The Cube Root Of Entropy exhibition, Rothman Gallery, Sculpture Garden, Stratford, Ontario, August 1970

Intermedia at Stratford: “The tendency to play”

artscanada

art and ecology theme issue

August 1970

by John Noel Chandler

John Chandler, a frequent contributor to arts-Canada, is Director of Exhibitions for the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

John Chandler, a frequent contributor to arts-Canada, is Director of Exhibitions for the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

Since brass, nor stones, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’er sways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

- Shakespeare

I have never felt any antagonism for or anxiety over the anarchy represented by the prevailing forms of art; on the contrary, I have always welcomed the dissolving influences. In an age marked by dissolution, liquidation seems to me a virtue, nay a moral imperative. I have always looked upon decay as being just as wonderful and rich an expression of life as growth.

- Henry Miller

Euripides wrote in his Bacchae that the man who pursues a greatness which endures is apt to miss those things which are present and close at hand. In this age of wastefulness and non degradable throw-aways, it is a relief to find artists who care not for greatness or endurance, who do see the ephemeral, flowerlike beauty of things which are present, and who are concerned that the materials which they use are reprocessed, recycled and reused.

A group of Intermedia people from Vancouver assembled an environment at Rothmans Art Gallery titled The Cube Root of Entropy. Entropy, a term borrowed from the Greek word for transformation by mechanical engineers, has undergone various transformations itself in the hands of Buckminster Fuller and Robert Smithson where it emerged as a new word for the pre-Renaissance belief that the world is running down – that things which are ordered have a tendency to seek disorder, and this is the way it is used for this exhibition.

When Intermedia arrived in Stratford, they assembled minimal, geometric sculptures out of cardboard cubes (boxes) stapled together. The boxes were made to the artists’ strict specifications and wax coated on the exterior faces. When I saw the exhibition, the sculptures were still in their pristine, geometric forms. Towering above the rest was a 24 foot high ziggurat, built in one day, its ivory surface beginning to take on the patina of Vermont marble from its exposure to the sun. Before the tower stood a six-foot chequered cube, made by alternating brown and white 12 inch boxes, six to an edge, chained with a chain of rectangular boxes to another chequered cube of the same dimensions but made by alternating brown and white 18 inch boxes, four to an edge. Further down the path rainbows arched over one’s bent head, each made with 36 specially designed rectangular boxes with one side an inch narrower than its opposite. Beyond the arches, and built the day I was there, the most popular piece was situated: a circle made by joining two of the rainbows together, sitting four feet high on its circumferential edge, containing a circle of grass. This little corral was just the right height for adults to lean on and contemplate the grass within; children had to be lifted by their parents to see what was inside. From this circle it was a short walk up a slight grade to my favorite piece – a box made with boxes containing boxes randomly thrown in and heaped up high above the edge. The container, its content, the material with which it was made (even its fabricators) were all boxes. In this piece not only was form and content the same, but indeed all of Aristotle’s four causes – the first, formal, material and final – were all one. I’d be tempted to say that boxes were Intermedia’s bag if they weren’t equally concerned with process and transformation, the dissolution and decay and corruption of these geometric forms into disorder.

Only the piece floating in the pond had begun to show decay, and even that might not have if it weren’t for the fountain which Inter-media had assumed would have been turned off for the summer. The water piece was also a chequerboard of alternating squares of mirrored mylar coated cardboard and bare water. The cardboard pads were originally attached corner to corner, though when I saw it several of the pads, especially those in the area of the jet fountain, had broken loose and drifted to the far corner of the pool where they were rapidly decomposing, their surfaces tarnishing with a rainbow iridescence like oil slick on water. Among them were the bloated bodies of several dead fish, presumably killed by the chemical added to the water to kill the algae which if permitted to live would have stopped up the fountain (perhaps there is a lesson in ecology here?).

Light waves bouncing off the water and pads were transformed electronically into sound waves. A light shower occurred while I was there, reducing the sound to a light hum, picking up again when the cloud passed, letting the sun shine in. At night the sculpture was lit with Dichromate lights, arranged at the edge of the pond in a repetitive series of red, amber, green and blue but blinking randomly which would radically alter the appearance of the work. A night-time visitor asked if the three dimensional pieces were lighted from within, apparently because the Dichrom lamps reflecting on the waxed surfaces made them appear to glow. Unfortunately, the last train to Toronto left before dark so that I was unable to witness the effect of the lighting. From the description, however, the lighting seemed more applied and less integral as a result than any other aspect of the environmental work – though, of course, it was concerned with another aspect of transformation and possibly added to the beauty of the spectacle. Since a considerable part of the intention was the process of change the works under-went during the course of the summer, these changes were to

have been well documented with photos and film.

However, a storm of

unforeseen violence hastened their process of decay by two months and

left hundreds of shredded and soggy boxes (and hundreds of “I told you

so’s”) in its wake. Nothing recognizable remained. What had taken only a

few days to make had, in Nature’s cataclysmic way, taken even less time

for time to destroy.

Now all that is left are the documents. Gary Lee-Nova, who had to return

to the milder climate of Vancouver, was philosophically resigned. Dennis

Vance and Box Arnold remained to see what could be salvaged. (Footnote 1)

Arnold hopes to install the photographs as monuments and memorials of

the sculpture on their previous sites. Photographs of the ziggurat are

to be mounted on a Plexiglas cube. The grass within the circle is to be

kept un-mowed throughout the summer as a memento. A 14 foot ziggurat will

be made on a new site, and a 60 x 80 inch photo mural of the two chained

cubes will be displayed. Photos and stills from film taken during the

storm and recording the decay will be used in the display.

The artists are now designing a cardboard which will endure longer than

that which they had used. There was a flaw in the design which left

unwaxed edges exposed to the moisture when assembled. These edges

literally drank the moisture from the surrounding air. The outer

protective wax simply served to retain the moisture which otherwise

might have dried up.

Vast yet airy and ephemeral, these sculptures stood in sharp contrast to

the small yet weighty and non degradable Rodin bronzes within the

gallery. In both, the materials seemed appropriate – bronze for the

heavy and serious; paper for the light and playful. Not that the bronzes

are incorruptible – the Bard of Stratford well knew that the bronze

monuments of past ages would not outlive his rhymes made with paper and

black ink.

It was the element of playfulness which most appealed to me in their

work … a playfulness which was very nearly childlike. The ecologist

Edith Cobb wrote, “The tendency to play may be said to be characteristic

of animals reared in a nidicolous (i.e., a specifically nest-like)

domestic ecology.” (Footnote 2) This morning I watched a sparrow playing

with a white, downy feather. She would drop it, circle and arc while the

feather fluttered, and then swoop down before the feather landed on the

mud flat and catch it in her bill. She repeated this many times, each

time letting it drop a little further, making a bigger and bigger circle

and testing the full limit of her skill. At length she missed and flew

off looking for something else to do. Was this unlike the lives of

artists? What toy have children enjoyed more than cardboard boxes? Toys

never last; if sturdily built they soon outlive the child’s interest in

them. Let us build our art out of cardboard and write our criticism on

the sands of ocean beaches.

I am not yet convinced, however, that entropy is a fruitful concept for

art. I should prefer that artists stood their ground against the

inclination toward disorder. Aristotle saw the motivation for art in a

desire to cheat death – to leave something of oneself behind, like

children. Sexual activity may be sublimated art activity; making love a

substitute for making art. Heraclitus wrote that “all is flux,” yet this

fragment is timeless. And even Miller, who preferred to write about

decay as content strove for a form that was firm: “it is in the

vitality, the durability, the timelessness and changelessness of the

thoughts and events that I plunge anew each time . . . there is nothing

really vague or tenuous – even the nothingnesses are sharp, tough,

definite, durable.” The concern for documentation – words, film, photos

- denies the intention of impermanence in most current conceptual and

ecological works.

And as for the ecology … it is fine to want the material reprocessed, but this has more to do with conservation than ecology, which is the study of the relations between organisms and their total environment. It includes conservation but is not coextensive with it. The use of natural forces and the recording of their effects is also related to the ecologist’s attitude – that man must live with nature, in nature, and not attempt to dominate it nor exploit it. Yet the episode of the storm and the artists’ response to it shows that they are still not free from the Western concept of man being in competition with nature. The ecology of Intermedia’s environment is rather to be found in the artists’ plasticity of response to the outer world, “the ability to perceive as a child and to participate with the whole bodily self in the forms, colours and motions, the sights and sounds of the external world of nature and artifact.” (Footnote 3) If it weren’t for that it would have been better to have the trees back in the forest than have the cardboard environment in Stratford and these pages about it in your hands. It is startling to think that if I had conserved a few words a fir or hemlock might still stand tall in the forest.

Footnotes 1. Dennis Vance rebuilt the chequerboard water piece in eight foot squares, grommeted on each corner. 2. Edith Cobb, “The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood,” Daedalus 88 (3): 537-548, Summer, 1959, reprinted in The Subversive Science, Paul Shepard and Daniel McKinley, editors, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1969. In this important essay Miss Cobb also argues that individualism needs rethinking and reshaping, that “know thyself” is no longer a useful psychosocial concept… an idea related to the desired anonymity of the Intermedia group, I think. 3. Cobb. 4. The Intermedia show was sponsored by the Canada Council for the Arts; Crown Zellerbach Canada Ltd. fabricated the specially designed boxes. The Vancouver artists who participated in the show were Box Arnold; Gary Lee-Nova; Dennis Vance; Ken Ryan and Al Hewitt.

Photograph of The Chubby Checker Memorial courtesy of Gary Lee-Nova