Almanac spirit fine

by JOAN LOWNDES

The Vancouver Sun: Thursday, April 8, 1971

B.C. Almanac is here at last—that is at the Vancouver Are Gallery. But it has been available all across the country in bookstore since last November, for in the minds of the artists who participated, their 15 bound photo-books constitute the real exhibition.

There are no original glossies on the walls of the VAG, only photos of the pages in the book. In the spirit in which the whole enterprise was conceived, this review is being written from the book.

It is not a coffee-table production. It will never, like one of Roloff Beny’s creations, be chosen as the most beautiful book of the year nor is it priced upwards of $30. A lot of altruism went into its compilation. For $6.95 one has access to almost 1900 photos printed on the cheapest paper possible and on one of B.C.’s own products: newsprint. The thinking behind this relates to anti-precious, anti-elitist ideas shared by many artists today. Public response so far according to local bookstore has been good.

Almanac was commissioned by Loraine Monk of the stills division of the National Film Board, who made $17,000 available to co-ordinators Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy. They simply let as many people as possible know about the project— poets, photographers, designers, artists— and out of many meetings the concept of the book-as-exhibition grew. Each participant was given total freedom both in subject matter and the lay-out of the 81/4” by 101/4” page.

The mass production process was then set in motion. Seven tons of stacked raw newsprint, as documented on the cover of Almanac, were delivered to the small Brock Webber printing plant.There, working within the 11 tonalities of the Kodak grey scale which forms the spine of the book, master printer Rob Brown performed heroically.

Many of the photos are experimental: there are inserts, overlays, blurred moving figures. Newspapers would reject them outright But Robbie Brown, working with special inks to permit maximum contrast in black and white, allowed the photos to come to life with a richness and subtlety one would not have believed possible on this type of paper.

As a tribute to him the artists put his smiling face on the poster for their premiere showing last November in the Photo Gallery of the National Film Board in Ottawa. Oddly enough in all the fracas about nudity in certain scenes, it was in the end the poster that was rejected by the National Film Board. As one of those who had fought the censorship battle said to me wearily at the time: “Oh I guess they had to say ‘No’ to something.”

What then of the nudity? There is nothing to surprise anyone who goes to the movies. Moreover there is in it not so much a frankness— for that word has assumed unpleasant military overtones— but a naturalness which is characteristic of the younger generation. When my mother was pregnant she waited for nightfall to go for a walk, all muffled up in a great overcoat. I was at the ballet the night before my daughter was born.

Now young fathers like Michael de Courcy and Peter Thomas are photographing their pregnant wives nude. It is logical that in their realization of the importance of process, whether it be from tree to printed photograph or from womb to baby, they should look with renewed wonder at the body’s preparation for reproduction. It is important for the woman that she be envisaged not as deformed but as a ripened seed ready to burst. All the photographs of her have this quality of respect for life, as do those of babies breast-feeding. How many Madonnas and Child have we not seen in this pose, including one in which the Virgin’s milk is so abundant that it squirts in the eye of an onlooking saint?

There are elements of eroticism in the book as there are throughout the history of art, but to me many of the photos of nude men and women in the sea express rather the innocence of an Eden before the Fall.

What the Almanac reflects most clearly is attitudes towards life. It is to be hoped that George Woodcock will see it, for to be leave that by some stroke of fate, one’s own generation is the last to have a feeling for beauty is to be plunged into the deepest misanthrope.

Fortunately the young men and women who took these photos— most of them are young— are not reading what Aldous Huxley wrote 50 years ago. They are pointing their cameras at the sky, the grass, their new born babies, rocks, cook-outs, friends, people young and old, and finding a kind of beauty. They could all echo the passionate cry with which Judith Egglington begins her photo-book: I am a living creature.

Each one, however has a different imagery, for when it was decided to use newsprint the empathic was thrown not on technique but on actual content, on what one had to say. Sometimes this proved disappointing.

Chris Dikeakos’ drive through the east End of the city does nothing to make these familiar streets more interesting, while Jack Dale’s girl hitch-hikers and beach beauties spliced in with totems do not really work. His most beautiful double page is that in which somewhat like McLaren in his Pas de Deux but without the same definition, he overlays several movements of a nude dancing, surrounding her with nebulae.

One of the outstanding contributions to Almanac, however is de Courcy’s Season Cycle, a chronological account of the birth of his daughter Koko. The treatment jus cinematographic. Certain images, such as home made-bread and flowers, recur rhythmically. Figures move into close-up from a distance. Some shots are composed with exquisite sensibility while others have a “caught” quality, adding up to a freedom of handling that has great authority.

Another highlight is Glenn Lewis’ Seashells in the Forest at Storm Bay with Bedroom, a theme with variations related in feeling to his film Forest Industry. His two “posed” shells, on different trunks and in different plays of light on leaves, have it in the lower corner and insert of his bedroom, with debris washed into it like sea rack after a storm. This memory of his room at the New Era Social Club in Chinatown, persisting deep in the seclusion of the forest, is a moving poetic image.

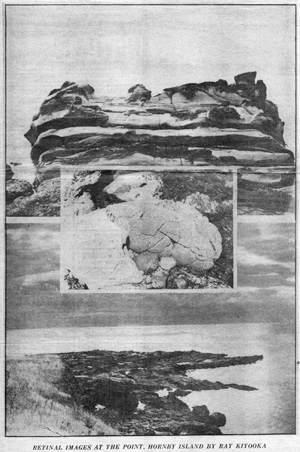

Kiyooka also yields to the power of the landscape in his Retinal Images of The Point, Hornby Island. His sculptural concerns are evident in his sensitivity to rocks, they're pittings, erosions, almost feminine roundness, and their monumentality. He often pairs images, linking them with a smaller inset Polaroid.

Kiyooka also yields to the power of the landscape in his Retinal Images of The Point, Hornby Island. His sculptural concerns are evident in his sensitivity to rocks, they're pittings, erosions, almost feminine roundness, and their monumentality. He often pairs images, linking them with a smaller inset Polaroid.

Peter Thomas deals with the nude in unusual fashion by having his model roll in the sand so that the pattern of her skin pblends with the bark of a tree.

Gerry Gilbert builds three-layer collages across both pages of this book, in which sequences of form, relationships of light and shade, are controlled with the with the utmost finesse.

Jone Pane in her Projections, puts the thoughts of her people into comicstrip balloons in a way that is rather obvious. Vincent Trasov, in an unconscience homage to the American painter Jim Dine, has photographed the favorite clothes of people on hangers. Limp or jaunty they are extremely expressive, although a great deal of their meaningfulness depends on knowing the people involved.

Michael Morris, in what resembles a series of stills, shows to male nudes on the beach, one “drawing” on the other with the light reflected from a small mirror. The N.E. Thing Co.'s documentation assumes almost too much knowledge of its activities – such as the memory of its portfolio of photographs of piles – and where it has printed a sheet of 30 photos, they obviously become so small as to be almost illegible.

Tim Porter is concerned with reality as we scan it from buses and cars, peoples faces cut off, out of focus. He is also interested in the long bleak perspective of apartment house corridors, in the kind of life people lead behind a fine stonewall surmounted by a hedge. Always whether people are present or not, they are implicit.

Robertson Woods’ Snap Shots, laid out eight to a page, again record the very free artists lifestyle on the West Coast, but coming where they do as the last of the 15 photo books, they do not add anything that has not already been said.