B.C. Almanac(h) C-B is an anthology of 15 West Coast Canadian artists' booklets, and an exhibition. Commissioned by the National Film Board of Canada in 1970, the project was created, designed and produced by Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy.

Contributing artists:

Jack Dale

Michael de Courcy

Christos Dikeakos

Judith Egglington

Gerry Gilbert

Glenn Lewis

Taras Masciuch

Michael Morris

N. E. Thing Co. Ltd.

Roy K. Kiyooka

Jone Pane

Timothy Porter

Peter Thomas

Vincent Trasov

Robertson Wood

Video:

B.C. Almanac(h) C-B Exhibition,

National Film Board Gallery, Ottawa, 1970

Opening night remarks by Mrs. Doris Shadbolt / Vancouver Art Gallery and Mr. Peter Bunell / Museum of Modern Art, NYC

© 1970-2014 Gerry Gilbert and Michael de Courcy

Gerry Gilbert describing the BC Almanac to students at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in 1989

“A big fat book of photographs from Vancouver – it went all over the world. It was like: Ah ha! In modern photography there’s Vancouver – the BC Almanac. It accepted everything from salon photography to a poet’s snapshots.”

B.C. Almanac(h)C-B, re-drawing the map

by Michael de Courcy

August 2015

In January 1970, Loraine Monk, executive director of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) Stills Division, invited Vancouver artist/photographer Jack Dale to help facilitate a long overdue NFB Stills survey of photographers from Canada’s West Coast. Jack in turn asked me to partner with him in the development and production of the project. We were given a budget of $17,000 and the assurance that as co-producers and artists we would have full creative control.

In January 1970, Loraine Monk, executive director of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) Stills Division, invited Vancouver artist/photographer Jack Dale to help facilitate a long overdue NFB Stills survey of photographers from Canada’s West Coast. Jack in turn asked me to partner with him in the development and production of the project. We were given a budget of $17,000 and the assurance that as co-producers and artists we would have full creative control.

Jack and I had recently exhibited together in the group exhibition Photography Into Sculpture produced by MoMA, NYC. We had also previously collaborated as members of the artist collective, Vancouver’s Intermedia Society.

The collaborative art, being produced at Intermedia in the late 1960s challenged the traditional definitions separating various fine art disciplines as inflexible obstacles in the free exploration of ideas. When figuring out what to do for art and how to do it Intermedia artists were inclined to create their own rules of engagement, re-drawing the disciplinary map as the work unfolded. If need be, painters could be filmmakers; photographers might explore the possibilities of the performing arts, etc.

In our early discussions about the project, the notion of mounting a conventional exhibition of pictures was quickly eclipsed by the idea of publishing a series of artist-produced books of photographs printed on newsprint and distributed widely at newsstands.

As this somewhat radical plan for the project became public we found that those who “got it” got involved and those who didn’t weren’t interested and didn’t show up. In this way, the process of grouping together the 15 artists whose work became what was to be known as the B.C. Almanac(h)C-B, seemed relatively automatic. By including a painter, a poet, a sculptor, a dancer we created a diverse group, many of whom were not primarily photographers. The common thread uniting the project being ‘artists with cameras’.

Each artists was simply asked to design and produce a 20- or 40-page camera-ready manuscript of photographs on whatever subject he or she might choose— there were no other guidelines.

We wanted the exhibition to highlight the link between the publication of artists’ photography and the idea of consumer accessibility associated with popular media items such as comic books and magazines.

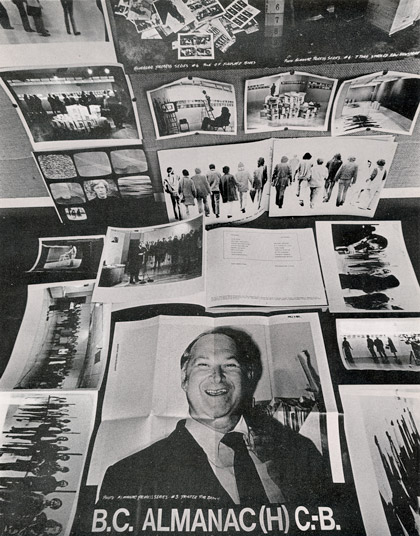

The B.C. Almanac(h)-CB gave participating artists un-mediated access to the apparatus of the printing and publishing industries. Photographic evidential reference to the process of printing and publishing (Almanac Process Series, No. 1-6) was incorporated directly into the design of both the book and gallery installation. In the book, images on the cover, spine, back cover and title pages highlighted stages of this production process. On the cover, tons of sheeted raw newsprint was depicted stacked on the factory floor prior to being shipped to the printer. The spine bore an image of a printer’s 11 step greyscale, universally used to decode a photographic image and adapt its range of tones to that of the offset printing process. Inside, on the title pages and endpapers, an image of the British Columbia wilderness forest represented where the pulp for the newsprint paper for the book originated; a portrait of our printer, Robbie Brown represented our personal engagement with the industrial printing process; and group picture of the 15 artists re-enforced the nature of a collaborative community. Finally, on the back cover, a picture of a pile of printed booklets attests to the transformation of the artists’ photographic ideas into mass media.

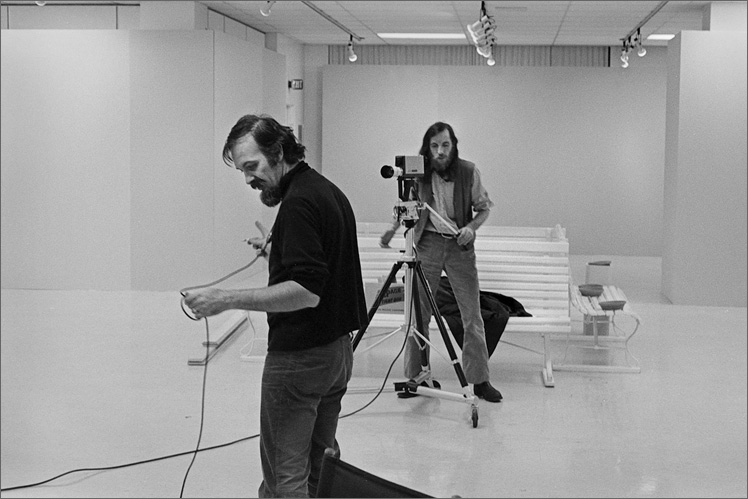

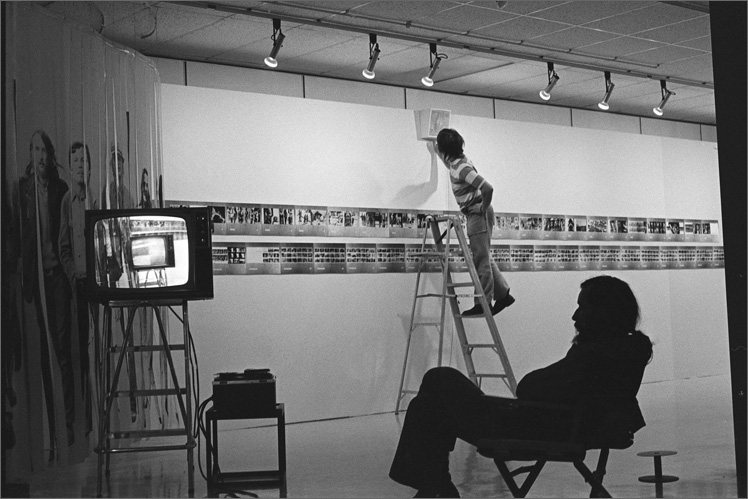

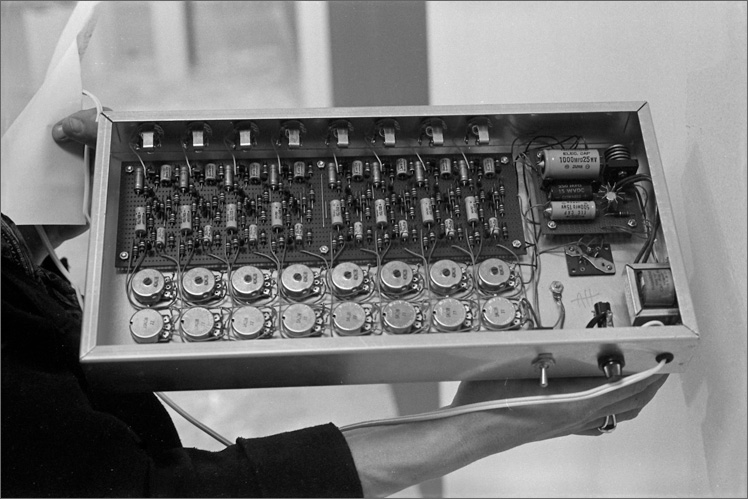

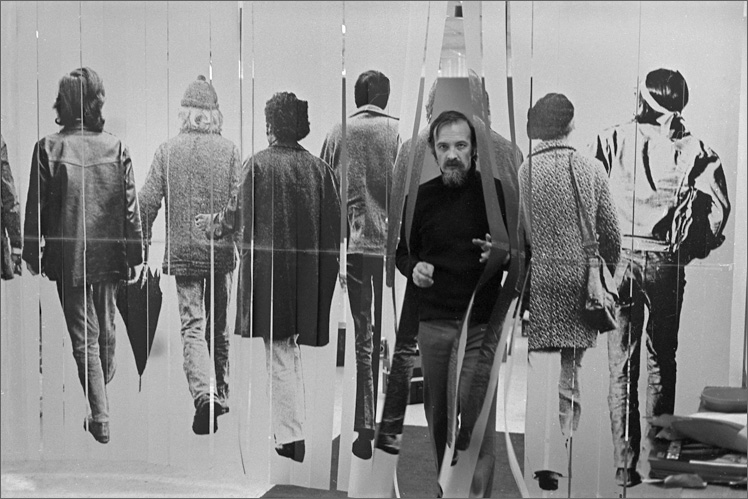

A week before the scheduled opening, on Friday November 13th, Jack Dale, Gerry Gilbert, Dennis Vance and I descended on the NFB Stills Division photographic gallery on Kent Street in Ottawa to install the multimedia BC Almanac(h)-CB show. We were armed with 11 shades of custom grey-toned wall paint, Intermedia’s brand new, state-of-the-art Sony video AV-3400 Portapac, and a 15 channel sound system custom designed and created for the installation by sound sculptor Dennis Vance. Our mission, for this friendly occupation of the Gallery, was to transform the space into a floor-to-ceiling greyscale environment complete with interactive sound, while video-documenting the entire process for our version of “the making of” movie.

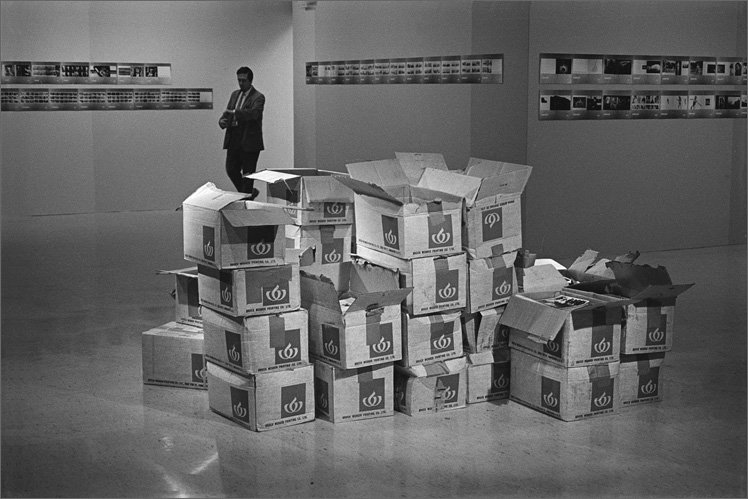

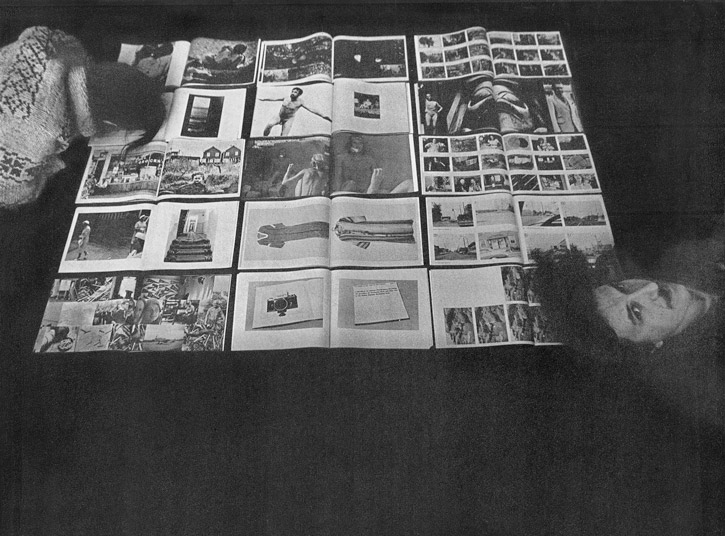

Apart from several examples of the camera-ready manuscript pages there were no original photographs in the show. The art on the walls consisted of scaled down photographic reproductions of pages from the book. The central space of the gallery was given over to a monumental stack of cardboard boxes containing hundreds of the printed Almanacs along with a video monitor playing a looped audio and video montage created from material captured and submitted by each of the almanac artists as part of their story. The installation was as much a book launch as it was an exhibition.

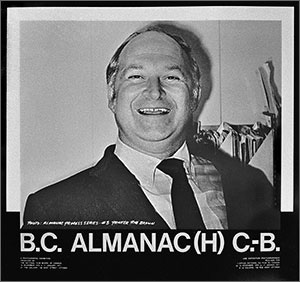

Up to the very opening hour there were tense, ongoing, government-level discussion centred around the possible obscenity issues which might be triggered by the avalanche of frontal nudity featured in the book and exhibition. Also in contention was the apparently offensive (to the NFB executive) BC Almanac(h)-CB poster image of our smiling printer Robbie Brown. Finally, not without irony, at the 11th hour, we were given the green light to proceed as planned on the condition that we not display the poster of Robbie Brown.

The exhibition subsequently traveled to The Edmonton Art Gallery and The Vancouver Art Gallery. The original B.C. Almanac(h) C-B at 435 pages and 1600 photographs was printed in an edition of 5000. In 1970 it sold for $6.95 in bookstores across Canada. A recent online search for the book came up with an average price of $600US for a first edition copy in reasonable condition.

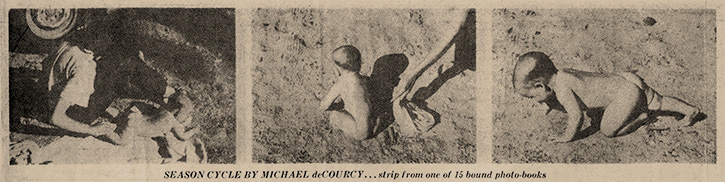

Detail from Season Cycle, Lorene and Koko, 1970

Why hippy photography is not dead and you just are...

by tyler jean mcGackin

September 2015

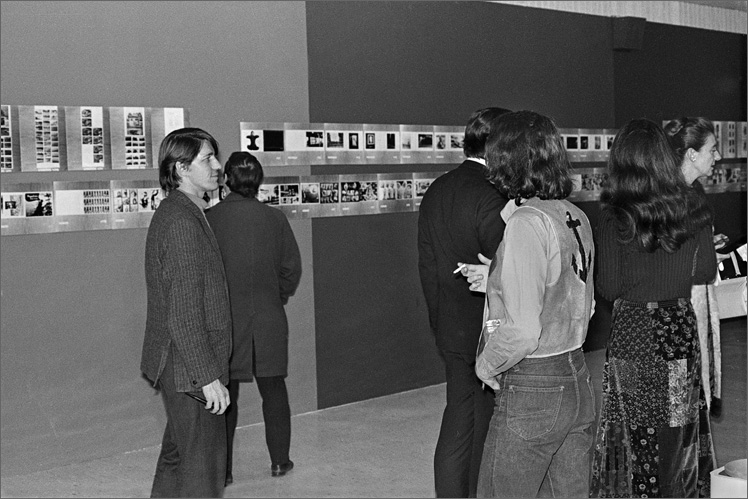

The BC Almanac(h) C-B installation at the New York Art Book Fair, MoMA PS1, 2015

One summer a few years ago I phoned a professor who, after an hour or so of talking, goes, “listen, we’ve gotta look at hippy photography, we’re losin’ it, man!” I didn’t think she necessarily meant photos from the 60’s but rather the devices, drive, that unadulterated and human impulse to document that generation--now kind--of forgot. “It’s done, man, it’s totally dead, and you’ve all missed out,” she repeated. The statement lingered though this “hippy” photography idea had not materialized in my own understanding or practice of art making.

And perhaps, out of divination, or chance, fate, once I had started to embrace this almost innate process that I happened into the B.C. Almanac. In a room at MoMa Ps1’s Printed Matter’s book fair I had stopped in my tracks. Shocked-- seconds prior I wanted to get the fuck out, stop browsing through these crowded corridors with the loud music that spoke only of the event, not the objects themselves. Okay, it’s a party, an affair to which New York’s pseudo art--world pretentiously migrates, congregates, Queens is the place to be in mid--September. But I kept thinking about the 50’s, 60’s and all that reactionary work which-- having indebted myself in art theory and a New Wave cinema class-- once engaged a discourse between the intellects and artists of the time. I mean, What are we going to learn here, now, in 2015, but aesthetic and quality? Who cares?

[Worse, my friends had been hurriedly waving me down to move on, get over this or that room, as if they too have been sucked into speed and frustration. We ain’t got no money to buy these books anyways.]

But this room in particular I did not leave. I could not leave. Goosebumps bumbling down my side. I’m intrigued, rubbing at my chin and circling round a pile of brown cardboard boxes stacked three or four feet high, falling over, strewn about, overflowing with thick newsprint books, posters seeming outdated, unfamiliar, unedited, done by hand and pen, not morbidly simplified or pointing to the resin coating on a picture--less sheet of matte paper. It’s human, analogue, the grain of 35mm ecstatically putting static in my brain that screamed “touch me, just damn touch me, bend over, pick me up.” I’m satisfying my libido with warmth, nostalgia, I don’t desire anything but this pile, which only encourages me to contemplate. It new for me, but old in that I smell Sunday morning news, my grandfather’s paper unfolding onto his lap. It’s of a different time, a different temperament, unstuffy. How perfectly out of place.

MoMa Ps1 reminds me of NYC parks tonight. On one hand you have the rush--rush rooms with copious amounts of dead--end books, like a Madison Square Park in the spectrum of parks. But then you have Thompson Square Park; history, transit, leisure, enclosures, the rules of no rules and what chaos can become. The B.C. Almanac room has two wide entryways on either side and a completely open space on the front, they're the fork in the road. But no, they do no succumb to disregard, instead they opt to hang a large, grainier photo of what--appear--to--be hippies. People walk by, don’t stop, there are two people running this booth. They look at me, but they’re surprisingly welcoming, not harsh, fixated on a telephone as I’ve learned to anticipate. And again I’m thinking this is damn cool, this is what’s missing, this is real, tangible, yes! Score! High five me friends!

And in the book is the automatic “hippy” photography my professor once tried to explain, said I’d missed out on. I’m told that this is the first reprint of the fifteen-- artist collaboration since the 1970’s. I’m invited to flip through 450+ pages, but as I do a wave of relief washes over.

The images themselves are the exhibition, and this space merely emphasizes this sacred almanac. I’m experiencing the lives of distant strangers I’m never to meet. Viewing life via the scribes of a generation mystified. The liberation, love, mundanity and soul of life profoundly illustrated here, on paper, in a book. I believe it was enlightenment which I'd experienced standing there. I felt my throat closing and skin chilling, on brink of tear. Is this revelation? I even did a little dance... Really, I’d found what it was that I was missing, that New York was missing, what may or may never occur again: Genius. And B.C. Almanac saves the show.

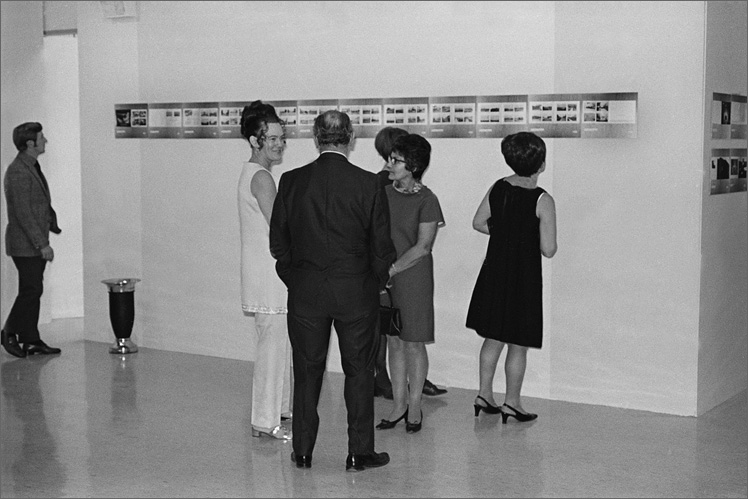

At the Photo Gallery of the National Film Board,

Ottawa November 1970 to January 1971

by Barry Lord

artscanada February to March 1971 p.p.’42-45

At least since impressionism photography has been mid-wife at the birth of most of the new art forms that matter most; yet photographers themselves have usually been paradoxically anxious to be accepted on traditional terms into the very temple of the fine arts they have been helping to undermine. Now at least come indications — the Gar Smith slide show last season and the B.C. Almanac process this one— that young artists are willing to use photography to help create a mass-production art of public distribution in which the image is everything and the precious object for exploitation and possession doesn’t exist at all.

At least since impressionism photography has been mid-wife at the birth of most of the new art forms that matter most; yet photographers themselves have usually been paradoxically anxious to be accepted on traditional terms into the very temple of the fine arts they have been helping to undermine. Now at least come indications — the Gar Smith slide show last season and the B.C. Almanac process this one— that young artists are willing to use photography to help create a mass-production art of public distribution in which the image is everything and the precious object for exploitation and possession doesn’t exist at all.

Almanac process is the execution by 15 photographers of an exhibition-Cum-set-of-books of photographs collectively and bilingually entitled B C Almanac(H) -CB. Originally produced for the National Film Board stills gallery in Ottawa, where it opened in November, it will also be presented at the Vancouver Art Gallery in April. The book-set, available loose in a box or bound in a single volume, is being circulated by the N.F.B. as the eight in its series of Image photo-books; the Museum of Modern Art is also selling it. Signally each of the books cost 50c, the set sells for $6.95 for all 15 books. The comparatively, low cost was achieved by printing the hundreds of photographs (often nine or 12 to a page) on perishable newsprint. On the gallery walls, instead of the glossy originals to which the book would be secondary, are only photographs of the book pages; looking at this “exhibition” produces, if anything, a desire to see the books themselves. Thus the true nature of the camera art is recognized: the reproduction for mass distribution comes first, and the “photograph as object” is only a record of it.

This kind of fidelity to process provided a rational for ill aspects of production. The gallery walls in Ottawa were painted in the series of greys of the photographer’s grey scale, and the spine of the bound volume had the same motif. A picture of the requisite semen tons of newsprint stacked in the printer;s shop graces the cover of the bound set; and the invitation to the Ottawa showing as well as the title page of the bound book offer a glorious photo of the B.C. forest from which the pulp for that newsprint came. The artists also wanted to use the grinning face of their printer as the photo for the shows poster, but Film Board director Sydney Newman who allowed plenty of pubic hair and nipples and pregnant nudes in the show and the book, censored this head-and-shoulders shot of the grinning Rob Brown, on the grounds that it would harm the Board’s public image . “Liberal” values and “good taste,” in art as in government remain the enemy.

In many ways the Almanac process was yet another product of the Intermedia group. Dennis Vance supplied responsive electronic sound for the Ottawa exhibition, and Gerry Gilbert closed the extended-almanac cir cute by taking videotape of the opening. Much of his tape showed the playback TV unit itself, sometimes while it was telecasting one of the tapes that the artists had made in Vancouver. Many of them have been at one time or another associated with Intermedia, and while the organizers Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy are recognized as photographers, a good number of the others — Roy Kiyooka, Michael Morris, Ian Baxter’s N.E. Thing Co., Glen Lewis and Gerry Gilbert– are primarily known for their work in other art forms.

Jack Dale”s Totems and Judith Egglington’s I am a living creature both look comparatively conventional, with their expressive inter-relation of images. Vincent Trasov’s dead-pan pix of his own and his friend’s favourite clothes on a hanger (an unacknowledged homage to Jim Dine) and Robertson Wood’s Snap Shots with eight or nine or a dozen pix to a page in family album fashion, suggest much more clearly the tone of Almanac as a whole.

The approach to subject-matter, needless to say, is documentary. Ian Baxter simply records some of the N.E.Thing Co.’s photographic projects. Michael Morris gives us a series of shots of two male nudes seated among rocks, one with his back to us reflecting the light from the sun onto the other’s body; they could well be stills from a film. Roy Kiyooka photographs rock formations on Hornby Island that look like his sculpture, adds some nude and clothed figures that happened to be there with him, and is careful to include a few shots with polaroid prints scattered over the landscape.

Allowing artists to do the layout led to an intriguing multiplicity of ways of relating to such images. Timothy Porter contents himself with one-to-a-page presentations of his matter-of-fact shots of bus interiors and hotel corridors. Glenn Lewis in-sets a littered bedroom interior shot in the corner of a series of pictures of “posed” seashells in forest settings. Jone Pane puts her “projection” images into a comic-strip “thought” bubble, inside the “projecting” picture. And Gerry Gilbert allows his personal sensibility to control every connection of subject and form in his three tiered collage pages.

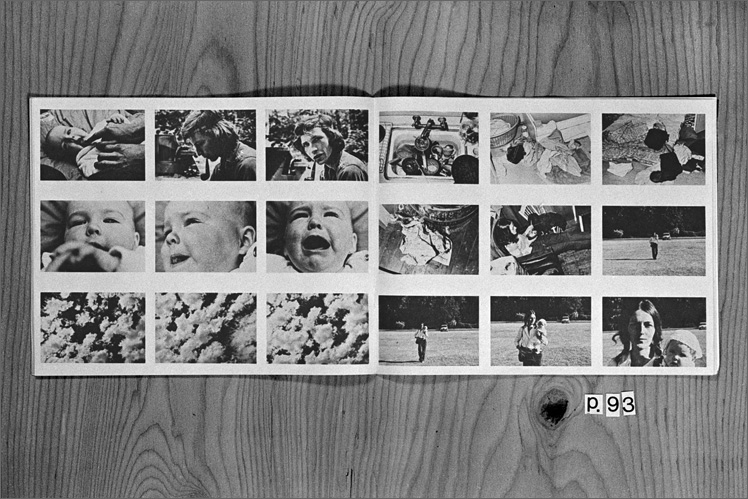

Curiously, the most consistent applications of the philosophy seemed to me the best and the worst books in the set. Christos Dikeakos’ documents of a drive through Vancouver streets, displayed four to a page, were consistent enough but absolutely vapid. Michael de Courcy’s nine-to-a-page document of the birth of a daughter, of the other hand, is the most moving and completely satisfying book in the set. Entitled Season Cycle, it includes many individually beautiful photos on its way from early pregnancy through the delivery room to the bonneted, crawling infant and beyond to the mother back in the sea. Over it all de Courcy maintains an open as-it-comes vigilance that re-enforces the real-life narrative and allows the telling images as if naturally into his lens.

Curiously, the most consistent applications of the philosophy seemed to me the best and the worst books in the set. Christos Dikeakos’ documents of a drive through Vancouver streets, displayed four to a page, were consistent enough but absolutely vapid. Michael de Courcy’s nine-to-a-page document of the birth of a daughter, of the other hand, is the most moving and completely satisfying book in the set. Entitled Season Cycle, it includes many individually beautiful photos on its way from early pregnancy through the delivery room to the bonneted, crawling infant and beyond to the mother back in the sea. Over it all de Courcy maintains an open as-it-comes vigilance that re-enforces the real-life narrative and allows the telling images as if naturally into his lens.

In all, Almanac(h) is undoubtedly the most advanced show of the current season, conceptually. It confirms once more that it is through photography today that significant art forms can be created. But it also, inevitably, points to a problem: birth cycles and beach parties are groovy, but for artists arrived at this point of formal consciousness must there not also be an equal attention to content? This kind of public-document form demands a public-document to match – and something a bit less banal than a drive through Vancouver. The assignment to match public art forms with adequate public content seems to me to be at the top of the artists agenda for the early 1970s.

Forest image used for invitation to opening of BC Almanac(h)-CB

Photographs by Tamio Wakayama

"Gerry Gilbert & Glen Lewis"

"BC Almanac(h)-CB collected ephemera"

Almanac spirit fine

by JOAN LOWNDES

The Vancouver Sun: Thursday, April 8, 1971

B.C. Almanac is here at last—that is at the Vancouver Are Gallery. But it has been available all across the country in bookstore since last November, for in the minds of the artists who participated, their 15 bound photo-books constitute the real exhibition.

There are no original glossies on the walls of the VAG, only photos of the pages in the book. In the spirit in which the whole enterprise was conceived, this review is being written from the book.

It is not a coffee-table production. It will never, like one of Roloff Beny’s creations, be chosen as the most beautiful book of the year nor is it priced upwards of $30. A lot of altruism went into its compilation. For $6.95 one has access to almost 1900 photos printed on the cheapest paper possible and on one of B.C.’s own products: newsprint. The thinking behind this relates to anti-precious, anti-elitist ideas shared by many artists today. Public response so far according to local bookstore has been good.

Almanac was commissioned by Loraine Monk of the stills division of the National Film Board, who made $17,000 available to coordinators Jack Dale and Michael de Courcy. They simply let as many people as possible know about the project— poets, photographers, designers, artists— and out of many meetings the concept of the book-as-exhibition grew. Each participant was given total freedom both in subject matter and the lay-out of the 81/4” by 101/4” page.

The mass production process was then set in motion. Seven tons of stacked raw newsprint, as documented on the cover of Almanac, were delivered to the small Brock Webber printing plant. There, working within the 11 tonalities of the Kodak grey scale which forms the spine of the book, master printer Rob Brown performed heroically.

Many of the photos are experimental: there are inserts, overlays, blurred moving figures. Newspapers would reject them outright But Robbie Brown, working with special inks to permit maximum contrast in black and white, allowed the photos to come to life with a richness and subtlety one would not have believed possible on this type of paper.

As a tribute to him the artists put his smiling face on the poster for their premiere showing last November in the Photo Gallery of the National Film Board in Ottawa. Oddly enough in all the fracas about nudity in certain scenes, it was in the end the poster that was rejected by the National Film Board. As one of those who had fought the censorship battle said to me wearily at the time: “Oh I guess they had to say ‘No’ to something.”

What then of the nudity? There is nothing to surprise anyone who goes to the movies. Moreover there is in it not so much a frankness— for that word has assumed unpleasant military overtones— but a naturalness which is characteristic of the younger generation. When my mother was pregnant she waited for nightfall to go for a walk, all muffled up in a great overcoat. I was at the ballet the night before my daughter was born.

Now young fathers like Michael de Courcy and Peter Thomas are photographing their pregnant wives nude. It is logical that in their realization of the importance of process, whether it be from tree to printed photograph or from womb to baby, they should look with renewed wonder at the body’s preparation for reproduction. It is important for the woman that she be envisaged not as deformed but as a ripened seed ready to burst. All the photographs of her have this quality of respect for life, as do those of babies breast-feeding. How many Madonnas and Child have we not seen in this pose, including one in which the Virgin’s milk is so abundant that it squirts in the eye of an onlooking saint?

There are elements of eroticism in the book as there are throughout the history of art, but to me many of the photos of nude men and women in the sea express rather the innocence of an Eden before the Fall.

What the Almanac reflects most clearly is attitudes towards life. It is to be hoped that George Woodcock will see it, for to be leave that by some stroke of fate, one’s own generation is the last to have a feeling for beauty is to be plunged into the deepest misanthrope.

Fortunately the young men and women who took these photos— most of them are young— are not reading what Aldous Huxley wrote 50 years ago. They are pointing their cameras at the sky, the grass, their new born babies, rocks, cook-outs, friends, people young and old, and finding a kind of beauty. They could all echo the passionate cry with which Judith Egglington begins her photo-book: I am a living creature.

Each one, however has a different imagery, for when it was decided to use newsprint the empathic was thrown not on technique but on actual content, on what one had to say. Sometimes this proved disappointing.

Chris Dikeakos’ drive through the east End of the city does nothing to make these familiar streets more interesting, while Jack Dale’s girl hitch-hikers and beach beauties spliced in with totems do not really work. His most beautiful double page is that in which somewhat like McLaren in his Pas de Deux but without the same definition, he overlays several movements of a nude dancing, surrounding her with nebulae.

One of the outstanding contributions to Almanac, however is de Courcy’s Season Cycle, a chronological account of the birth of his daughter Koko. The treatment is cinematographic. Certain images, such as home made-bread and flowers, recur rhythmically. Figures move into close-up from a distance. Some shots are composed with exquisite sensibility while others have a “caught” quality, adding up to a freedom of handling that has great authority.

Another highlight is Glenn Lewis’ Seashells in the Forest at Storm Bay with Bedroom, a theme with variations related in feeling to his film Forest Industry. His two “posed” shells, on different trunks and in different plays of light on leaves, have it in the lower corner and insert of his bedroom, with debris washed into it like sea rack after a storm. This memory of his room at the New Era Social Club in Chinatown, persisting deep in the seclusion of the forest, is a moving poetic image.

Kiyooka also yields to the power of the landscape in his Retinal Images of The Point, Hornby Island. His sculptural concerns are evident in his sensitivity to rocks, they're pittings, erosions, almost feminine roundness, and their monumentality. He often pairs images, linking them with a smaller inset Polaroid.

Peter Thomas deals with the nude in unusual fashion by having his model roll in the sand so that the pattern of her skin blends with the bark of a tree.

Gerry Gilbert builds three-layer collages across both pages of this book, in which sequences of form, relationships of light and shade, are controlled with the with the utmost finesse.

Jone Pane in her Projections, puts the thoughts of her people into comicstrip balloons in a way that is rather obvious. Vincent Trasov, in an unconscious homage to the American painter Jim Dine, has photographed the favorite clothes of people on hangers. Limp or jaunty they are extremely expressive, although a great deal of their meaningfulness depends on knowing the people involved.

Michael Morris, in what resembles a series of stills, shows to male nudes on the beach, one “drawing” on the other with the light reflected from a small mirror. The N.E. Thing Co.'s documentation assumes almost too much knowledge of its activities – such as the memory of its portfolio of photographs of piles – and where it has printed a sheet of 30 photos, they obviously become so small as to be almost illegible.

Tim Porter is concerned with reality as we scan it from buses and cars, peoples faces cut off, out of focus. He is also interested in the long bleak perspective of apartment house corridors, in the kind of life people lead behind a fine stonewall surmounted by a hedge. Always whether people are present or not, they are implicit.

Robertson Woods’ Snap Shots, laid out eight to a page, again record the very free artists lifestyle on the West Coast, but coming where they do as the last of the 15 photo books, they do not add anything that has not already been said.